The Richmond Slave Trail Commission released Tuesday a master plan for a potentially $150 million heritage site in Shockoe Bottom, including a slavery museum and African-American genealogical center [Times-Dispatch & NBC12]. The focus is on the site of Lumpkin’s Jail.

Lumpkin's Jail

I have closely followed the progress of the slave trail, I’ve photographed and studied it [slideshow], and I’ve admired the work of the Commission in creating and developing the 2.5 mile path retracing the steps taken by so many slaves during Richmond’s infamous time as a hub for slave trade. Here is an excerpt from Summer 2007 on the slave trail from the now expired DiscoverRichmond.com website:

The City Council established the Richmond Slave Trail Commission in the late 1990s to raise the level of awareness and informational accuracy about Richmond’s role in the slave trade. Although the first slaves arrived in Virginia in 1619, Richmond did not play a major part in the business of enslavement until after the United States banned the importation of Africans from oversees in 1808. Businesses emerged to fill the demand for the purchase, sale, and delivery of enslaved African-Americans.

Realizing a general lack of knowledge about the slave trade — once so integral to Richmond — the Slave Trail Commission developed a walking trail that would physically outline the paths countless slaves traveled on their demoralizing journey through forced servitude.

Research uncovered the existence of several dozen slave businesses in Shockoe Bottom along with the long-vanished Burial Ground for Negroes and the site of Lumpkin’s slave jail: the tragic landscape where many enslaved African-Americans were severed from their families.

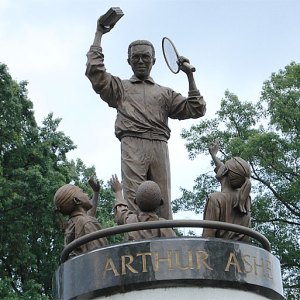

Reconciliation Statue

I was there to cover the unveiling of the Reconciliation statue [slideshow], which was dedicated March 31, 2007. It is a fitting tribute and a good addition to the slave trail. There are identical statues in Liverpool, England, and Benin, West-Africa — completing the triangle.

James River Park System manager Ralph White has been a huge proponent of the slave trail, and he has spoken with me about the efforts by his staff to ensure the trail is clean and cared for — above and beyond their call of duty, which is the norm for Ralph and crew.

Manchester Docks

In my efforts to help educate people with multimedia, I created a video (likely expired) that I was quite proud of that included an intro — from my kayak — approaching the Manchester Docks as if the camera was on board a slave trade ship arriving in Richmond. I remember that day well, and it gave me chills.

I’ve also walked the slave trail from the docks heading west, through the overhanging trees and thorny underbrush. Slaves were mostly transported at night so as not to disturb the people of Richmond. They were often badly malnourished, beaten and sick. If you walk the trail at dusk and darker, you can — if only for a moment — get a glimpse of what the slaves may have experienced as they were dropped into the New World.

Here is the text from the video, describing the trail [via RTD]:

1. Manchester Docks

In the pre-Revolutionary period Manchester was a busy slave market. Around 1776, the market moved to Richmond with the James River serving as a major avenue for transporting enslaved Africans.

2. Slave Trade Path

The Slave Trade path along the James River reflects the transition Africans had to make between their homelands and the strange new world. They quickly understood that their chained walk toward an unknown future held no promise and many dangers.

3. Mayo’s Bridge

John Mayo built his first toll bridge here in 1788 to connect Richmond and Manchester, and it has remained a crossing of the river ever since. On the north side of the river was the Shockoe Valley. The financial prominence of this part of the city dates to the 19th century, in which the slave trade and slave-financed industry generated exorbitant amounts of capital to be invested.

4. Kanawha Canal

The late 18th-century construction era required a large, mostly slave labor force. African-Americans dug the canal. Numerous African-American boatmen traversed the canal, while black Richmonders carted cargo to and from the boats. The canal became another means for shipping slaves.

5. Auction Houses

There were several dozen such houses in Shockoe Bottom, typically selling human “goods” along with corn, coffee, and other commodities. Some sales were part of a larger business; other auctioneers dealt exclusively in slaves. Most slave commerce was concentrated in the roughly 30-block area bounded by Broad, 15th, and 19th Streets and the river.

6. Reconciliation Statue

Identical statues in Liverpool, England, Benin, West-Africa; and Richmond, Virginia, memorialize the British, African, and American triangular trade route, now identified as the Reconciliation Triangle.

7. Lumpkin’s Jail

Enslaved Africans referred to Lumpkin’s Jail as “the Devil’s Half Acre,” reflecting the despair and anger of people separated forever from their families. In 1867, Mary Lumpkin, a black woman and widow of the jail’s owner, Robert Lumpkin, boosted post-Civil War black education when she rented complex to a Christian school, which evolved into Virginia Union University.

8. Negro Burial Ground

Many of Richmond’s first citizens lie in unmarked graves here. Richmond’s gallows was above on the hillside. Executed here was Gabriel, an articulate, literate 24-year-old blacksmith from Thomas Henry Prosser’s Brookfield Plantation. Gabriel and his colleagues believed that God’s laws entitled them to equal station with men and women of all races. They conspired in 1800 to take over the Virginia government in an extensive campaign, which was betrayed at the last minute.

9. First African Baptist Church

The First African Baptist Church was founded in 1841. The church became a center for Christian worship and an anchor for African-American community development at a time when gatherings outside for church were prohibited.

WHAT: Richmond Slavery Reconciliation statue.

WHAT: Richmond Slavery Reconciliation statue.

Comments & trackbacks